Acastus

Panel by Jacopo del Sellaio (c. 1465)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOverview

Acastus was the son of Pelias, the king of Iolcus known for dispatching Jason on his quest for the Golden Fleece. Acastus himself was a hero, if only by proximity: he took part in the expedition of Jason and the Argonauts as well as the Calydonian Boar Hunt, though he did not play an important role in either of these exploits. After Pelias’ death, Acastus ruled as king of Iolcus.

As a king, Acastus does not seem to have been remembered fondly. He tried to have the hero Peleus killed for supposedly trying to sleep with his wife, but Peleus escaped and punished Acastus by sacking Iolcus and, in some accounts, putting Acastus to death.

Etymology

The etymology of the name “Acastus” (Greek Ἄκαστος, translit. Ákastos) is uncertain. Some scholars have claimed it means “unstable” or “uncelebrated,” but these translations should probably be regarded with skepticism.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Acastus Ἄκαστος (Ákastos) Phonetic

IPA

[ah-KAHST-uhs] [ɑˈkɑst əs]

Attributes

General

Acastus was born into the royal family of Iolcus, a city on the coast of Thessaly. In most traditions, he eventually succeeded his father Pelias as king of Iolcus. In some accounts, Acastus also took over the neighboring kingdom of Phthia later in his life (see below). He may also have served as the king of Pherae, yet another city in Thessaly.[1]

Acastus himself had few defining characteristics. In one important artistic representation, he was shown with his horses, a detail that suggests he may have been regarded as a capable horseman.[2]

Iconography

Acastus was not a popular subject in ancient art. When he did appear, he was typically shown together with other heroes who, like him, had taken part in the expedition of the Argonauts, or else as a judge or spectator in scenes that depicted the lavish funeral games of his father Pelias.[3]

Family

Acastus belonged to the line of the Aeolidae, the descendants of the hero Aeolus. Acastus’ father was Pelias, a mortal son of the sea god Poseidon who became king of Iolcus. In what appears to have been the standard account, his mother was Anaxibia, the daughter of Bias.[4] But Apollodorus mentions an alternative tradition that made Acastus’ mother Phylomache, the daughter of Amphion.[5]

Acastus had several sisters, sometimes known collectively as the “Peliads.” Their names were Pisidice (or Pasidice), Pelopia, Hippothoe, and Alcestis.[6] An additional sister, Alcandre, is known only from ancient art.[7]

There is enormous confusion surrounding the name of Acastus’ wife. According to Apollodorus, she was called Astydamia.[8] Pindar, however, names Acastus’ wife as Hippolyta, the daughter of Cretheus.[9] In still other sources, she was Cretheis, daughter of Hippolyta,[10] or even Cretheis, daughter of Hippolytus.[11]

Whoever his wife was, Acastus had several children with her. His sons’ names were variously given as Actor (who was accidentally killed by the hero Peleus),[12] Archandrus,[13] Architeles,[14] Menalippus,[15] and Pleisthenes.[16] His daughters were Sterope,[17] Sthenele (wife of Menoetius and mother of Patroclus, Achilles’ companion in the Trojan War),[18] and Laodamia (wife of Protesilaus, the first Greek hero to die in the Trojan War).[19]

Mythology

Acastus and the Argonauts

Acastus’ father was none other than Pelias, the tyrannical ruler of Iolcus best known for sending his nephew Jason to fetch the Golden Fleece. Pelias was very protective of his power and feared that Jason would try to take over his kingdom. He hoped to get rid of his perceived rival by sending him after the Golden Fleece, which was kept in the remote kingdom of Colchis by Aeetes, a king just as tyrannical and protective of his property as Pelias.

The young Acastus, however, was eager to take part in what promised to be the greatest heroic exploit of his generation. Ancient accounts agree that he was indeed one of the heroes who sailed with Jason to Colchis on the ship called the Argo (from which the term “Argonauts” is derived).[20] In one account, it was Jason who convinced his cousin to join the expedition to spite his uncle Pelias:

“Alas! for those of us who have fathers or sons alive! Is this the ship in which we thoughtless souls are sent forth in the face of a clouded sky? shall the ocean spend its wrath on Aeson alone? shall I not snatch away the young Acastus to undergo the same fortunes and the same perils? Then let Pelias desire a safe voyage for the hated ship, and join with our mothers to appease the waves by prayer!”[21]

But though Acastus’ role as an Argonaut is well-attested, it was also largely inconsequential; in other words, he did not play an important role during the voyage. Soon after the Argonauts returned to Greece, Acastus ascended to his father’s throne in Iolcus—though the circumstances that led to this event were not necessarily happy for him.

Panel by Jacopo del Sellaio (c. 1465)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainAfter arriving in Greece and handing Pelias the Golden Fleece, Jason began plotting against the king. In some traditions, Pelias had murdered Jason’s family while he was away, so naturally Jason wanted revenge. In this he had the help of his new wife, the witch Medea, who had betrayed her father Aeetes by helping Jason steal the Golden Fleece.

According to the familiar tradition, Medea convinced Pelias’ daughters that she could restore the youth of their aging father. She cut an old ewe into pieces, boiled them in a cauldron, and enchanted her gory soup with herbs and incantations: out leapt the ewe, transformed into a young lamb! Convinced that Medea could work this same miracle on Pelias, his daughters did not waste any time cutting their father into pieces and casting him into the cauldron. But this time, Medea did not perform her magic, and Pelias died—murdered at the hands of his own daughters.[22]

After Pelias’ death, Acastus held funeral games to honor him. Many great heroes (including many of the men who had sailed on the Argo) participated in these games, which were regarded as especially notable in antiquity.[23]

As for the fates of Jason and Medea—the killers of Acastus’ father Pelias—there were different versions of what happened next. In what was probably the standard tradition, Acastus expelled Jason and Medea from Iolcus and took over his father’s throne.[24] In other sources, however, Jason gave Acastus the throne and left Iolcus of his own free will.[25]

The Calydonian Boar Hunt

According to Ovid, Acastus—like many of the other Argonauts—took part in the Calydonian Boar Hunt when Meleager, the prince of Calydon, needed help killing a fierce boar that was ravaging his father’s lands.[26] But as in the voyage of the Argonauts, Acastus did not really distinguish himself in this important heroic exploit.

Acastus and Peleus

Aside from his unremarkable stints as an Argonaut and a boar hunter, Acastus is probably best known in connection with the mythology of Peleus, a hero of a rather higher caliber. Peleus, like Acastus, had sailed with the Argonauts and participated in the Calydonian Boar Hunt. He distinguished himself among the heroes of his generation and, in some traditions, was rewarded for his valor with a divine wife, the Nereid Thetis. His son, the great Achilles, would become even more famous than he.

Acastus’ Wife

Peleus, for whatever reason, seems to have been prone to murdering people (usually by accident). After he killed his half-brother Phocus (whether accidentally or, as in some traditions, deliberately), he was exiled from his homeland of Aegina and traveled to Thessaly, where he was purified of his blood-guilt by the Phthian king Eurytion. But before long, Peleus killed Eurytion too (an accident that took place during the Calydonian Boar Hunt). This time, Peleus went to Acastus for purification.

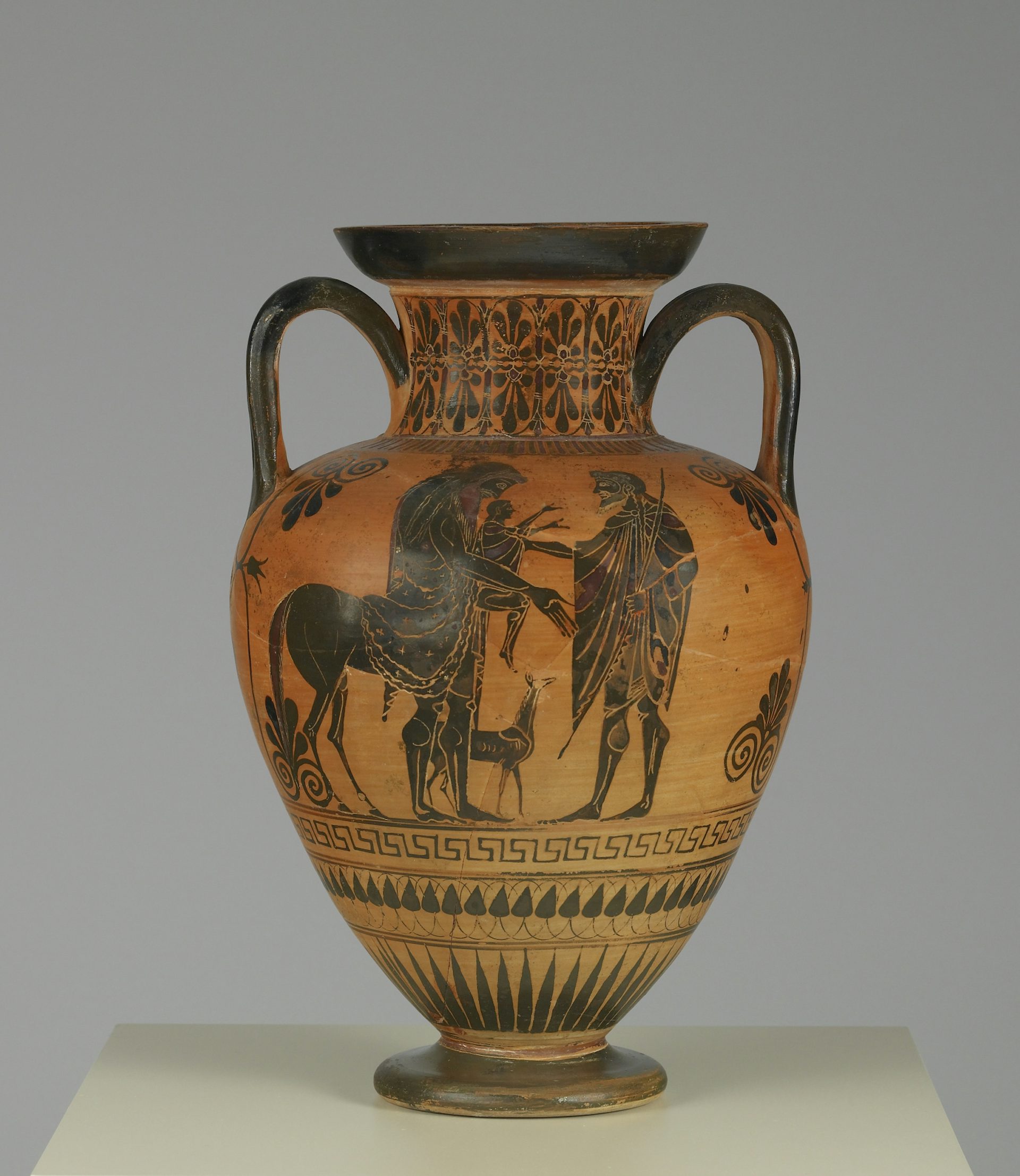

Black-figure neck amphora attributed to the Group of Würzburg 199 and the Antimenes Painter (ca. 520–510 BCE)

The Walters Art MuseumCC0While Peleus was in Iolcus, Acastus’ wife (usually called either Astydamia or Hippolyta) fell in love with the dashing hero. She tried to seduce Peleus, but he refused her advances. To punish him for this slight, Acastus’ wife told her husband that Peleus had tried to seduce her.

Acastus, believing his wife, wished to punish Peleus, but was reluctant to kill a guest. He solved his ethical quandary by taking Peleus hunting in the Centaur-infested woods of Thessaly. While Peleus was sleeping, Acastus hid the hero’s sword (in cow dung, according to one account) and left him to be murdered by the violent Centaurs. But the good Centaur Chiron rescued Peleus from his fate and restored his sword to him.[27]

Now it was Peleus’ turn to punish Acastus and his wife. He attacked Iolcus (either together with Jason and the Dioscuri or, in one account, all on his own) and conquered the city. He then killed Acastus’ treacherous wife; according to Apollodorus, he dismembered her and led his army into the city through her remains.[28] In some traditions, Peleus also killed Acastus.[29]

Peleus’ Kingdom

In one tradition, Acastus survived Peleus’ conquest of Iolcus and even lived to retaliate. Years later, when Peleus was an old man and his grandson Neoptolemus was away fighting in the Trojan War, Acastus drove Peleus out of his kingdom of Phthia (although in one variant, it was Acastus’ sons rather than Acastus himself who did this).

As it turned out, Acastus’ usurpation was ill-advised. Neoptolemus soon returned from Troy and restored his grandfather Peleus to the throne. In one account, he did this by killing Acastus’ sons; he would have killed Acastus, too, had not his grandmother, the goddess Thetis, put a stop to the bloodshed. Acastus was forced to turn Phthia over to Peleus and return to Iolcus defeated.[30]

Pop Culture

Acastus is not particularly familiar today, though he does feature in some contemporary adaptations of the story of the Argonauts. In such cases, he is usually depicted in a negative or ambivalent way, as a rather weak and even villainous figure. In the 1963 classic film Jason and the Argonauts, for instance, Acastus is sent by his father Pelias to sabotage the Argonauts. He even tries to steal the Golden Fleece himself, but is killed by the serpent Aeetes placed there to guard the fleece.